Maningrida: How it all began

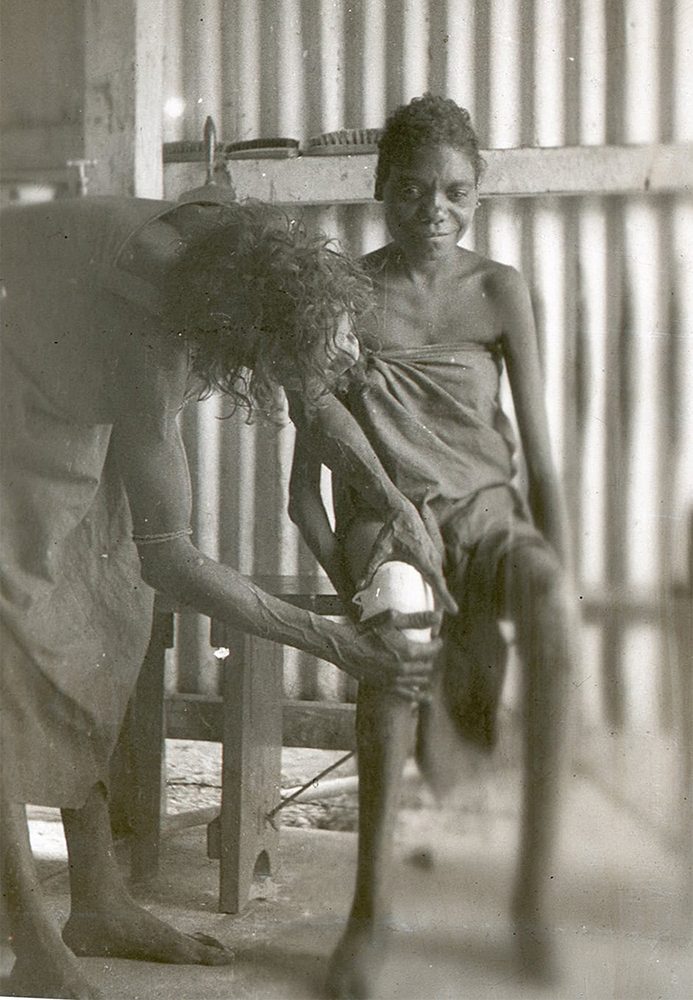

It was first recorded in 1937 that First Nations peoples were suffering from leprosy in Maningrida, an ‘Aboriginal’ settlement in the middle of the northern coast of Arnhem Land.

It took twenty years for the first doctor to arrive there. In 1957, Dr John Hargrave, a young medical graduate from the University of Adelaide, went by air to Goulburn Island then travelled to Maningrida by boat on the Liverpool River. “It was very remote – very remote indeed,” he told Caroline Evans years later in an interview.

Confronting the fear of enforced isolation

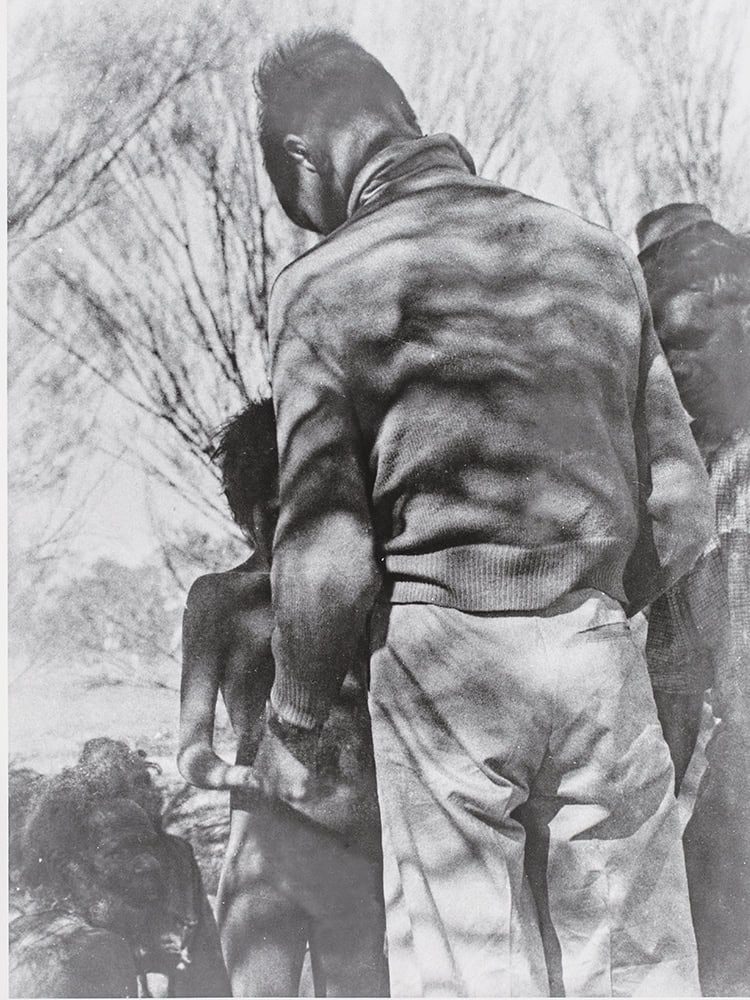

One of the first things John noticed in Maningrida was that many of the people suffering from leprosy were hiding in the bush. This was due to a policy of forcibly isolating leprosy patients. As there was no medical treatment available until the late-1940s, they would be removed from their families and placed in isolation for the rest of their lives.

Dr Hargrave’s first self-assigned task was to quash the popular belief that leprosy patients should be treated like criminals and locked away from the rest of the world. Up until 1955, people with leprosy in the Northern Territory were taken to leper colonies on Channel Island and prior to that Mud Island. Then in 1955, the East Arm Leprosarium on the mainland was opened.

Instead of following common practice and forcing First Nations people into hospital, John spoke to his reporting doctor and together they agreed to wait for patients to request admission to the hospital themselves.

First Nations peoples begin making their own decisions

Two years later, thanks to John’s work, a temporary isolation camp was established in Maningrida and First Nations patients came in for treatment without threats or forced retention. An airstrip had been built and leprosy patients were flown to Darwin when they required medical assistance. The majority of these patients had serious nerve damage, and hand and foot deformities caused by leprosy.

In Maningrida, fewer First Nations peoples were hiding in the bush when they caught leprosy, and this decreased the spread of the disease. As John explained to Caroline Evans many years later, when it was common practice for leprosy patients to hide in the bush, their condition couldn’t be seen and was, therefore, not treated. It then spread more rapidly among families and communities.

The First Nations peoples grew to trust and respect John, as he rallied against the police force to stop mandatory isolation. His insightful actions also eliminated the need for leprosy patients to hide in the bush. It turned out that Maningrida was where John would make one of the most important decisions of his life. It was there he decided to specialise in leprosy, and do everything he could to repair deformities such as claw hand, claw toes, foot drop and saddle nose.

How did leprosy reach Australia?

In 1872, gold was discovered at Pine Creek in the Northern Territory and, in 1884, pearls and pearl shells were found in the Darwin Harbour. These events led to an influx of European and Chinese immigrants who brought foreign diseases into Australia. The worst of these was leprosy, which was incurable at the time.

The disease eventually spread into First Nations communities and the Australian authorities took no notice of the nerve damage and deformities it was causing. By 1957, when Dr John Hargrave arrived, leprosy had reached epidemic proportions.