Dr John Hargrave's mission

It was first recorded in 1937 that a lot of First Nations people were suffering from leprosy in Maningrida, in Arnhem Land.

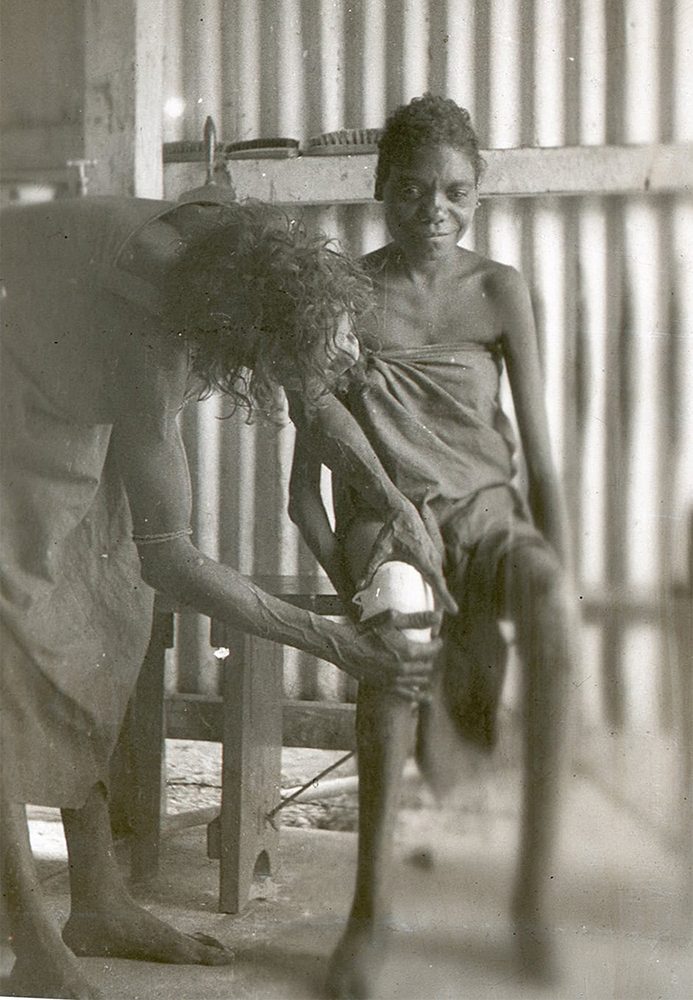

It took twenty years for the first doctor to arrive. In 1957, Dr John Hargrave, a young medical graduate from the University of Adelaide, arrived in Maningrida by boat on the Liverpool River. He had a strong yearning to practise medicine and just eighteen months of clinical experience.

Confronting the fear of enforced isolation

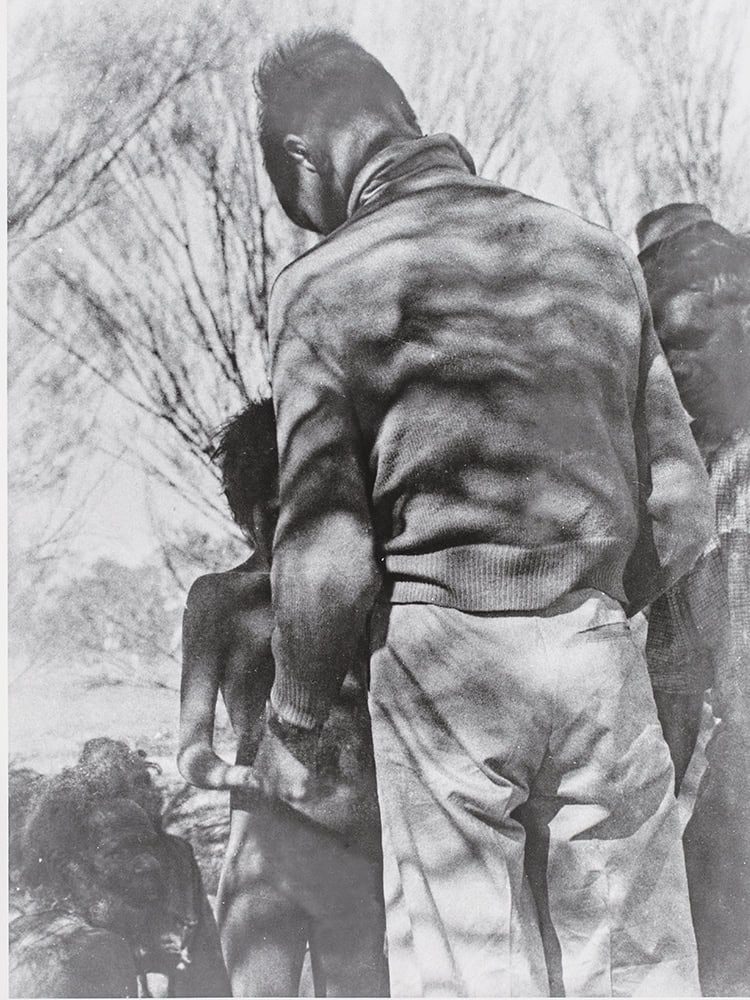

One of the first things Dr Hargrave noticed in Maningrida was that many of the people suffering from leprosy were hiding in the bush. This was due to a policy of forcibly isolating leprosy patients. As there was no medical treatment available until the late-1940s, they would be removed from their families and placed in isolation for the rest of their lives.

Dr Hargrave’s first self-assigned task was to quash the popular belief that leprosy patients should be treated like criminals and locked away from the rest of the world. Instead of following common practice and forcing First Nations people into hospital, he spoke to his reporting doctor and together they agreed to wait for patients to ask if they could go to the hospital.

First Nations people make their own life decisions

Two years later, a temporary isolation camp had been established in Maningrida and First Nations patients came in for treatment without threats or forced retention. An airstrip had been built and leprosy patients were being flown to Darwin when they required medical assistance. The majority of these patients had serious nerve damage and hand and foot deformities caused by leprosy.

In Maningrida, fewer First Nations people were hiding in the bush when they caught leprosy, and this reduced the spread of the disease. As Dr Hargrave explained in an interview many years later, when leprosy patients hide in the bush, their leprosy can’t be seen and is, therefore, impossible to treat. It then spreads more rapidly among their families and the communities they visit.

The First Nations people grew to trust and respect the young doctor who rallied against the police force to stop mandatory isolation, and who eliminated the need for them to hide in the bush. Maningrida was also the turning point in Dr Hargrave’s life. It was in Maningrida that he decided to specialise in leprosy and repair the deformities it caused.

How did leprosy reach Australia?

In 1872, gold was discovered at Pine Creek in the Northern Territory and, in 1884, pearls and pearl shells were found in the Darwin Harbour. These events led to an influx of European and Chinese immigrants who brought foreign diseases into Australia. The worst of these was leprosy, which was incurable at the time.

The disease eventually spread into First Nations communities, and the Australian authorities took no notice of the nerve damage and deformities it was causing. By 1957, when Dr John Hargrave arrived, it had reached epidemic proportions.

Channel Island – The Leper Colony

Watch the video to learn about the forced isolation of First Nations leprosy patients on an island in the Darwin Harbour.

From 1931 to 1955, people suffering from leprosy, predominantly First Nations peoples, were forcibly removed from their families and isolated on Channel Island in the Darwin Harbour. Just 10 kilometres from Darwin, the conditions and facilities were primitive and overcrowded.

During the 1950s, the number of people living with leprosy on Channel Island reached 250, including 45 children. More than 140 people died and were buried on the island in shallow unmarked graves. Some of these burial sites were marked with upturned beer bottles as recent as six years ago.

In 1955, Channel Island was closed as a leper colony and the patients were moved to a new facility on the mainland known as the East Arm Leprosarium.

East Arm was custom built with modern kitchens and bathroom facilities, and comfortable living quarters. It was staffed by nursing sisters from Daughters of our Lady of the Sacred Heart.